Limitations Aren't Supposed to be Fatal Flaws

Modern research papers showcase a neat trick. No matter how badly designed, poorly conceived, horribly executed, painfully unrealistic, or deeply unnecessary your actual study may be...none of that matters provided you complete the limitations section.

No, really, it's true. Once you label something a limitation, it's acknowledged, and once acknowledged, it's no big deal. Consumers of your research, like dogged journos, can still celebrate your findings. Maybe, if the journos have some ethics, they'll hedge, but whatever they do certainly won't make the headline, and no one will remember or care much about it. And other researchers can still liberally cite from your paper to build a super credible literature review in support of whatever they wish.

A related move is to do a correlational study, warn everyone that it's just correlational so causality cannot be determined, and then get your press release team on the case asap, knowing full well that everyone will infer causality regardless. But that's a subject for another day, maybe.

I can't speak with any institutional authority, being just some random dude, but I'm pretty sure that limitations sections were not intended to function as a dustbin into which you tossed everything bad about your paper, all of which, thanks to convention, magically turned into water under a bridge.

There's a thing, and I'm sure there's an official name for this thing, but there is a thing whereby grifters challenge their audiences to accept their critics' arguments. Seems risky, but the strategy works because people apparently believe that if you're aware of criticism against you, then that criticism cannot be legitimate because liars and cheats dodge accusations of wrongdoing. They certainly don't engage it.

Let's go out on a limb and imagine a crypto crook. This isn't so much a scummy pastime anymore as a respectable occupation and so he doesn't feel bad about fleecing grandma's nest egg or an entitled millennial's 401(k). All goes well until he's getting accused on Twitter of "scamming," and wouldn't you know it but the same trolls are popping up on his YouTube comments, and there's even an article about him on MarketWatch. All this negative publicity is starting to boil over, sort of like the planet because of all the fucking pointless crypto mining, not to mention every other dumb decision human beings make every goddamn day.

He's got a couple of choices. He can continue ignoring it, which doesn't seem to be working...OR...he can make a video about it. That'll make him look honest, he decides, showing he's not afraid of the criticism.

"Sure you could say that Captain Blackbeard was a scammer, he even killed people."

And then in the video he admits that some people are saying all sorts of things, like he's scamming, like his coin doesn't really exist, like you're not allowed to cash out, like you don't have a bank account anymore because his software installed malware on your device, like you're technically wanted in Thailand for money laundering and a little murder-for-hire.

The switch comes when he welcomes you to trust the haters, the jealous, the poor, in fact the actively poor, that is the people who hate money and light it on literal fire, and the fiat dogmatists who naively believe that money cannot simultaneously be currency, commodity, investment, life coach, and religion. And isn't everything a scam, really? What line do we draw? They say Bitcoin's a Ponzi scheme. Fine, maybe it is. But what's the stock market if not a Ponzi scheme? Come to think of it, what's life but a Ponzi scheme, in which children have to support their increasingly useless and leafblower obssessed elders?

By confronting the criticism, though probably not actually answering any of it, the scammer awkwardly situates the viewer. Wouldn't a dishonest person embrace silence? Besides, isn't there some law that would prevent him from doing whatever it is he's doing? Surely he must be trustworthy.

I'm not arguing that researchers are frauds or cheats for how they arrange their limitations sections. I'm only saying that these sections function similarly to the acknowledgment of our hypothetical scammer friend above, who's absolutely not based on anyone real.

Because, see, when your argument or study or whatever has a fatal flaw, that is, a thing which renders your conclusions unsupported, acknowledging it doesn't help. It just shows you're aware of it. It doesn't mean you answered it.

Let's illustrate

This was a massively popular study by the CDC on masking. In no time at all, its altmetric score (why is the CDC posting this?) soared off the charts. The study was so big on Twitter that I wouldn't be surprised if it had become a majority shareholder in the company—if corporations can be People, and indeed are in many ways superior to actual, real people, then why can't articles? This was the study people cited to prove the effectiveness of masking. Sure, it wasn't a randomized controlled trial, so it lost some points for that, but it qualified as empirical research.

The problem is that it does not isolate masking. Masking is not some behavior randomly distributed in the population, completely disconnected from other important unobserved variables. Like, people who mask, a priori, are expected to adopt other safety precautions, lowering their risk of COVID-19 infections. Before I was vaccinated, if I had go in public I freaking double masked, and you know what my main precaution was? Not going out in freaking public.

What this tells me is that people who claim to mask—and, again, claim to mask, as the data are all self-reported—were less likely to test positive for COVID-19. But, like, duh, obviously. The people who wear N95s to grocery stores don't behave like people who forgo masks altogether or those whose face bandanas technically satisfy their state-wide mandate.

The authors understood this criticism as well as anyone, so they put it right in the limitations:

The findings in this report are subject to at least eight limitations. First, this study did not account for other preventive behaviors that could influence risk for acquiring infection, including adherence to physical distancing recommendations. In addition, generalizability of this study is limited to persons seeking SARS-CoV-2 testing and who were willing to participate in a telephone interview, who might otherwise exercise other protective behaviors. Second, this analysis relied on an aggregate estimate of self-reported face mask or respirator use across, for some participants, multiple indoor public locations. However, the study was designed to minimize recall bias by enrolling both case- and control-participants within a 48-hour window of receiving a SARS-CoV-2 test result. Third, small strata limited the ability to differentiate between types of cloth masks or participants who wore different types of face masks in differing settings, and also resulted in wider CIs and statistical nonsignificance for some estimates that were suggestive of a protective effect. Fourth, estimates do not account for face mask or respirator fit or the correctness of face mask or respirator wearing; assessing the effectiveness of face mask or respirator use under real-world conditions is nonetheless important for developing policy. Fifth, data collection occurred before the expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant, which is more transmissible than earlier variants. Sixth, face mask or respirator use was self-reported, which could introduce social desirability bias. Seventh, small strata limited the ability to account for reasons for testing in the adjusted analysis, which may be correlated with face mask or respirator use. Finally, this analysis does not account for potential differences in the intensity of exposures, which could vary by duration, ventilation system, and activity in each of the various indoor public settings visited.

Oh, at least eight limitations. Comforting.

We see our criticism first: the study "did not account for other preventive behaviors."

That's not just any old limitation. That's not like patient attrition. That's not like applying a survey instrument to a population for which it was not expressly designed.

It's a fatal flaw. We can't make any judgments about the effectiveness of masking in a study like this, yet that's exactly what the CDC did as well as the paper's many disciples. You don't get to reincarnate a fatal flaw as a "limitation" and then draw whatever conclusion you want. I mean, you do. You did it. You even made a nice infographic for everyone to share, and everyone did indeed share it.

But you shouldn't.

I'll paraphrase Avon schooling Marlo.

Let me help you find your tongue. You trying to fast track this paper, so you can get a line to the Twitter mob. You trying to get to the social media motherfuckers because if you can, you wanna cut the peer reviewers and all them other data thug bitches out the conversation. I mean, you a natural researcher, right?But this is the thing though and I mean, you know I'm with you on all that as far as it goes, you know. Authors definitely need to stick together, you know what I mean. And all the fuss about your p values and closed data, I say let bygones be bygones but fuck all them limitations.

That's just the way I feel about it.

There's always gonna be a p-hacker, man. No p-hacker, no game.

-Avon Gelman

So what kind of study would I design to gauge masking's effectiveness? I wouldn't. Because "research" isn't meant to, and should not, answer many important questions. Sometimes it's impossible, and no matter how long you listen to noise, it's still just noise. Maybe eventually it starts to sound like revelation, and maybe eventually you become Charles Manson, but it's still just noise you're hearing and now you're a serial killer.

Why do I suspect N95s reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2? Physics, precedent, and extensive safety testing. I don't need "research" to show me what I already know based on sound scientific principles. What about other kinds of masks? I don't know, but it's reasonable to assume that some filtration or obstruction somewhat prevents emissions and so somewhat reduces transmissions. How much, who knows. But I do know that a study won't tell me anything useful, given the maddening complexity of the dynamics at-play.

Hey, I'll give the CDC credit for using R. That's pretty cool.

I won't dwell on this one because I actually like a lot of Archambault's work, and I don't want to pick on her, and God knows my own work has loads of issues. But the line is just Too Good to resist.

"The major limitation of this study is its methodology" (p. 100).

That's like...

The major limitation of this cancer drug is that it isn't a cancer drug.

The major limitation of this car is that it doesn't drive.

The major limitation of this playground is that it's filled with toxic garbage.

The major limitation of this seltzer is that it's La Croix.

If a crypto scammer wrote a paper

I'm going to present a brief paper written by a cryptocurrency investor. I'd tell you their name, but they're apparently unpopular with several governments and even the common people right now, and so they've gone a bit incognito.

You can tell that I'm not all that wild about how researchers cite sources, either.

Investment returns are the goal of most, if not all, investors (Cramer, 2002). Historically, returns have come from three primary investment vehicles: real estate (Piketty, 2014), equities (Scorsese, 2013; Stone, 1987), and bonds (Schwab, 2022). These investments comprise the "traditional" asset class (Amin & Kat, 2003; Burniske et al., 2017; Campbell, 2005; Chen & Terrien, 2001; David, 2005; Greer, 1997; Gupta, 2022; Hao & Liu, 2009; Inderst, 2010; Kurka, 2019; YouTube, 2021).

However, these returns have been criticized for being exploitative (Chomsky, 1967-2022; Nie et al., 2022). Graeber (2018), for example, argued that "Bullshit Jobs" were invented in response to the growing capitalist pressure to maximize investment returns. Traditional asset classes have also been associated with higher rates of murder-suicide (Kopecky & Taylor, 2020), depression (Liu, 2015; Liu & Fan, 2022), poverty (Moser, 1998), and antisocial behaviors such as drug abuse and participation in organized crime (Chase, 1999; D'Andria 2011; Kruisbergen et al., 2015; Muntaner et al., 1998)

Recently, a new asset class has emerged called cryptocurrency (Damon, 2022; Diehl, 2021; Hoosier, 2010; Horowitz, 2017; Musk, 2014; Saylor, 2021; Turing, 1951; Zizzer Zazzer Zuzz, 1963). Cryptocurrency is based on blockchain technology and functions as an empowering asset class because it does not exploit labor (Boersma and Nolan, 2020; Mehra and Dale, 2020), it reduces the net energy load contributing to climate change (Batten, 2022; Polk, 2021; Truby, 2022), and it is a potential catalyst for world peace and the end of human suffering (Bent, 2021; Bijou, 2021; Dorsey, 2021). Further, cryptocurrencies do not depend on predatory banking institutions (Tierney, 2022). Instead, participants in the cryptocurrency marketplace can transact cryptocurrencies on Exchanges, which are "bullet proof" decentralized user spheres designed to amplify returns and facilitate transactions (Lielacher, 2022; Muncaster, 2022). Such exchanges are widely-regarded as safe and non-exploitative alternatives to traditional banking (Athanassiou, 2021; Auer et al., 2022; Demertzis & Wolff, 2018; Fantazzini & Calabrese, 2021).

More immediately, cryptocurrency returns consistently and significantly outpace those from traditional asset classes (Google, 2021; Morningstar, 2021; Yahoo, 2021). These returns have led to the creation of billionaires, many of whom are in undeveloped parts of the world, and thus cryptocurrencies have lessened global inequality (Mezrich, 2019). Many investors report gains in excess of returns from traditional asset classes and are able to fulfill several life goals such as retiring early and engaging in effective altruism (Brady, 2021; Faux, 2022).

Investors naturally wonder where they should place their earnings (Merkle & Weber, 2014; Outkast, 2006). This paper argues, and demonstrates through multiple modalities, that earnings should always be invested in cryptocurrencies, especially in "alt coins," which are cryptocurrency alternatives to mainstream coins (Hayes, 2015; Wisniewska, 2016). This paper proves through mathematical induction that gains from cryptocurrency will necessarily and inevitably outpace gains from traditional asset classes. It further supports this proof through deep learning neural network computer simulations. Finally, it reports on the positive results of a randomized controlled trial. Implications and conclusions are considered, which is that readers should invest their incomes and savings in cryptocurrencies; for convenience, the Author owns and operates an Exchange willing to facilitate such transactions.

The first part of this argument is a mathematical proof. A mathematical proof is a necessarily true statement due to its logical structure and has philosophical origins (Danto, 1964; Derrida, 1967; Hanna, 2002). This paper's proof is represented by Figure 1. Let the Greek symbols on the left-hand side of the equation equal cryptocurrency investment returns, and let everything on the right-hand side equal investment returns in excess of traditional asset classes. Per reductio, their equivalence becomes necessarily true, that is, cryptocurrency returns are equivalent to returns in excess of traditional asset classes.

Figure 1. A mathematical proof.

The paper's second argument involves a deep learning neural network computer simulation. Deep learning neural networking is a sophisticated form of machine learning which is superior to most other artificial intelligence algorithms as has been demonstrated through various validity checks (Calin, 2020; Quora, 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Computer simulations are a way to represent reality through computers (Borrelli, 2019). This paper's simulations were run on numerous Bitcoin mining machines infected with a global malware variant under the Author's control for a total processing power of six quadrillion FLOPS.

The simulations aimed to represent 500,000 "universes" in which investors placed a fixed amount of money in one of four possible investment vehicles: real estate, cryptocurrency, equities, or bonds. The investment horizon was set to 100 years and several demographic variables believed to be of import to a person's investment acuity were also assigned (Aristotle, 2010; Gall, 2007; Grable, 1997). Age was excluded as a demographic variable for its purported insignificance in high-stakes decision making processes (Barthes, Derrida, de Beauvoir, Dolto, Foucault, & Sartre, 1977).

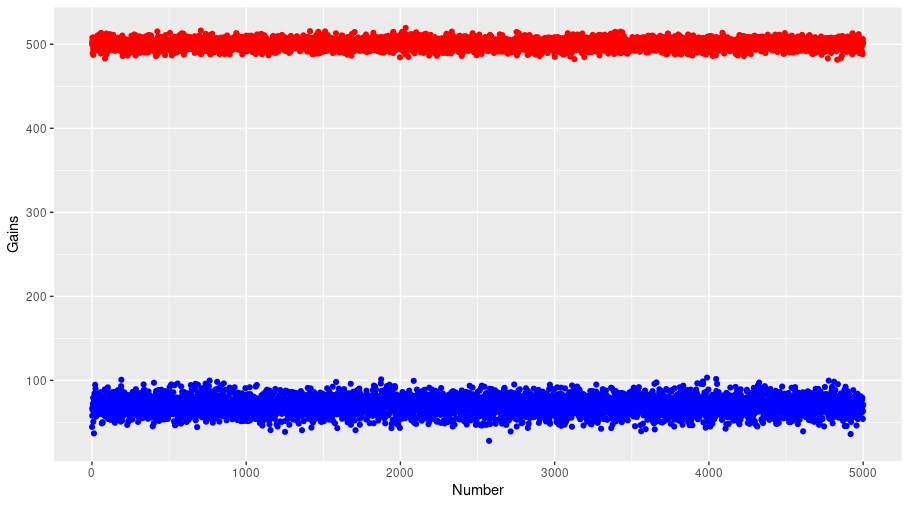

In all of the 500,000 universes, cryptocurrency gains outpaced those of the other asset classes, lending durable computer simulated support to this paper's main thesis. Specifically, the annual real return from cryptocurrencies was 205.67881911%; equities were 4.8541%; bonds were -1.2555512%; and real estate was inf, due to the collapse of a publicly-open real estate market from volatile conditions, namely terminal nuclear war. As this result could not be interpreted, I chose to omit it from the analysis; note that the passive income classes were designated as robust to apocalyptic living conditions, and so they were not affected. These differences were all extremely statistically significant (p < .00000001) and post-hoc tests (Tukey, 1949) showed that the cryptocurrency gains were similarly significantly different from all other asset classes. Figure 2 presents a 5,000 simulation sample of cryptocurrencies to equities.

Figure 2. Cryptocurrency (red) gains vs equities (blue) gains.

However, the average return of cryptocurrency is misleading, as it conflates popular coins such as Bitcoin and Ether with altcoins. On their own, altcoins returned an average annual yield of 387.1124859%, a statistically significantly higher (p < 0.00000001) yield than the aggregate for cryptocurrency.

The third proof is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The RCT is seen as the "gold standard" of scientific evidence (Smith & Pell, 2003; Yeh et al., 2018). Findings derived from RCTs are those which account for randomization and thus differences between the examined groups come from the treatment assignment (Hariton & Locascio, 2018). A total of 34 investors known to the Author were assigned, at random, to invest a sum of money (1,000 USD) in one of the following investment vehicles: Bitcoin, BND (an index fund for bonds), VOO (an index fund for the S&P 500). The trial's data collection period ran from July 1, 2021 to November 12, 2021. This data collection period represented a highly statistically significant period of time (p < 0.00000001). The Bitcoin investors made statistically significant higher returns (p < .00000001) than investors in the other asset classes, with very tight 95% Confidence Intervals.

This paper has a few limitations. First, the mathematical proof may have been extracted from a popular online social media forum and not constructed in response to the paper's argument. Second, the data from the computer simulations may have come from conditions favorable to the cryptocurrency investment vehicles, that is, parameters may have been affixed to guarantee that cryptocurrency returns would exceed returns from the other asset classes. Third, the sources cited may have been "cherry-picked" (Mayo-Wilson, 2017), that is, they may have been collected to advance a narrative sympathetic to cryptocurrency, and in some cases they may be misrepresented or inapplicable. Fourth, the randomized controlled trial may not qualify as a randomized controlled trial, and the data collection period of the trial may have been determined retrospectively. Fifth, there were no robustness checks conducted, though they would not have substantially changed the paper's findings.

In conclusion, cryptocurrency returns will outpace returns from traditional asset classes, as demonstrated through various evidence conduits. A mathematical proof was presented in support of the argument. Further, in not one of 500,000 computer simulations did a traditional asset class outperform cryptocurrency. Finally, a randomized controlled trial, the "gold standard" of scientific evidence (Smith & Pell, 2003; Yeh et al., 2018), showed overwhelming support for the thesis over a statistically significant period of time.

Given that human beings are rational actors (Rubin, 1998; Slovic, 2000), and that it is rational to want more than less money (Bezos, 2022; Dvorsky, 2014; Kahneman and Tversky, 1979), it stands to reason that a major implication from this paper is that human beings should invest in cryptocurrency and especially in altcoins. For convenience, the Author owns and operates a highly-rated Exchange on which cryptocurrency can be transacted and profit can be engineered.